The Warburg Effect: Cancer's Metabolic Signature

In the 1920s, Otto Warburg noticed something strange about tumors.

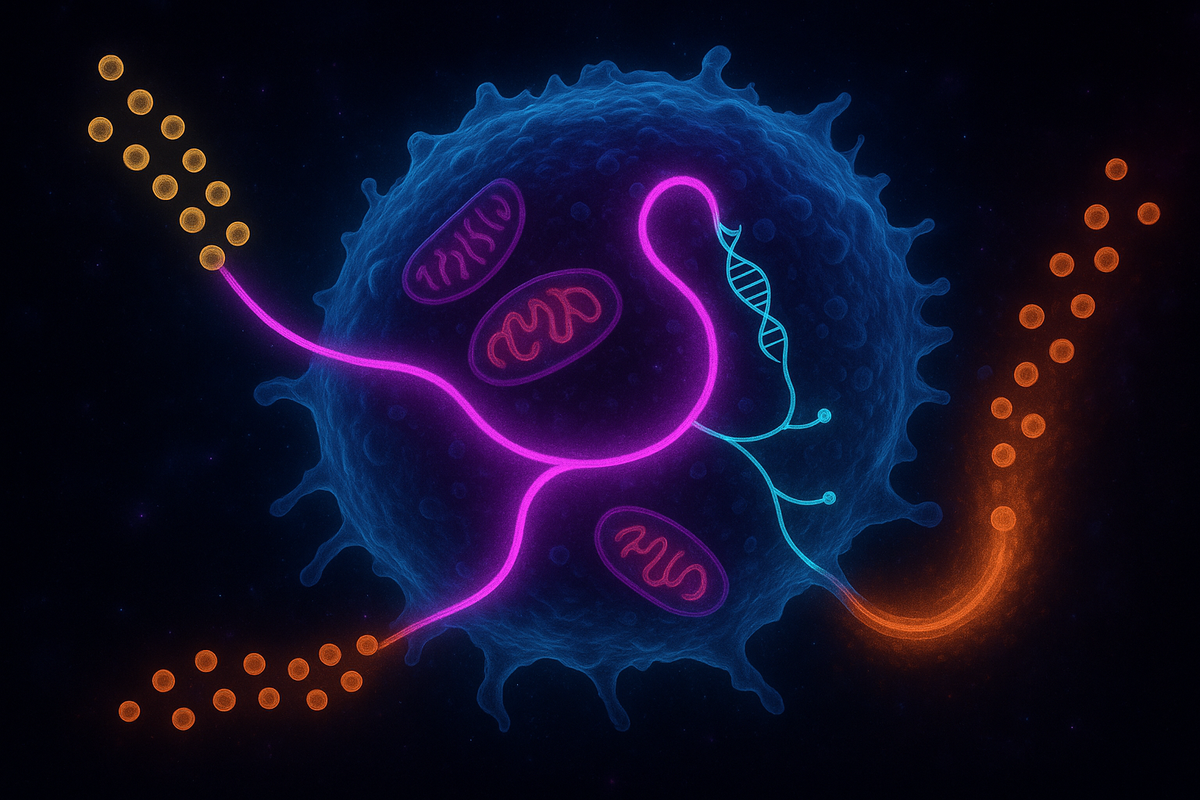

Cancer cells were consuming glucose at an astonishing rate—far more than normal cells. And they were fermenting it to lactate, even when oxygen was plentiful. This made no biochemical sense. Fermentation yields only 2 ATP per glucose. Oxidative phosphorylation yields 30-32. Why would rapidly dividing cells, which need lots of energy, choose the less efficient pathway?

Warburg believed he'd found the cause of cancer. Mitochondria were broken, he argued. Cancer cells couldn't do oxidative phosphorylation, so they fell back on glycolysis. Fix the mitochondria, cure cancer.

He was wrong about the cause. But his observation—now called the Warburg effect—was real, and it's become one of the defining features of cancer biology. Nearly a century later, we're still arguing about what it means.

Cancer cells ferment glucose even when they could respire it. This inefficiency is somehow advantageous. Understanding why is understanding something deep about what cancer is.

The Observation

Let's be precise about what Warburg observed.

Normal cells, when oxygen is present, fully oxidize glucose through glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation. The end products are CO₂ and water. ATP yield is high.

When oxygen is absent, normal cells switch to fermentation (anaerobic glycolysis). Glucose is converted to lactate. ATP yield is low, but it's better than nothing. This is what your muscles do during intense exercise when oxygen delivery can't keep up.

Cancer cells do something different. Even when oxygen is abundant, they preferentially ferment glucose to lactate. They produce lactate at rates 10-fold higher than normal cells, even in well-oxygenated tissue.

This is aerobic glycolysis—glycolysis in the presence of oxygen. The Warburg effect.

The cells aren't forced into this metabolism by lack of oxygen. They choose it. And they choose it at the cost of ATP efficiency.

Warburg's Hypothesis

Warburg proposed that the cause of cancer was mitochondrial dysfunction.

His reasoning: if cancer cells can't do oxidative phosphorylation properly, they have no choice but to rely on glycolysis. The metabolic shift isn't a choice—it's a necessity forced by broken mitochondria.

This idea was influential for decades but ultimately proved incomplete.

Problem 1: Cancer cell mitochondria often work fine. Many cancer cells have functional electron transport chains and can do oxidative phosphorylation. They choose not to. When glycolysis is inhibited, some cancer cells switch to respiration and survive. The mitochondria aren't broken—they're being bypassed.

Problem 2: The Warburg effect is a feature, not a bug. If aerobic glycolysis were just a desperate workaround, cancer cells should be at a disadvantage. But they thrive. Something about this metabolism is selected for during tumor evolution.

Problem 3: Oncogenes and tumor suppressors regulate metabolism. Mutations in cancer-driving genes directly alter metabolic pathways. The metabolic shift isn't a passive consequence of damage—it's an active, regulated response.

Warburg was right that metabolism matters. He was wrong about why.

The Biosynthesis Hypothesis

The modern explanation for the Warburg effect focuses on biosynthesis, not energy.

Cancer cells aren't just trying to make ATP. They're trying to make more cells. Rapid proliferation requires raw materials: nucleotides for DNA, amino acids for proteins, lipids for membranes.

Glycolysis generates biosynthetic precursors.

Glucose-6-phosphate feeds into the pentose phosphate pathway, producing ribose for nucleotides and NADPH for biosynthesis.

3-phosphoglycerate can be diverted to serine biosynthesis, which feeds into one-carbon metabolism for methylation and nucleotide synthesis.

Pyruvate can be converted to alanine, or enter the citric acid cycle to produce citrate, which is exported for fatty acid synthesis.

If a cell fully oxidizes glucose to CO₂, these intermediates aren't available. Glucose carbons become carbon dioxide—exhaled, gone, useless for building new cells.

The Warburg effect makes metabolic sense if you think of glucose as building material rather than fuel. Cancer cells extract building blocks from glucose, using glycolysis as a supply chain. The lactate they excrete is the waste product of this extraction.

Cancer cells choose inefficient ATP production because they're optimizing for something else: biomass.

The Overflow Hypothesis

Here's an alternative view: maybe aerobic glycolysis isn't strategic. Maybe it's overflow.

Cells can only run oxidative phosphorylation so fast. The electron transport chain has a maximum flux. When ATP demand is high and glucose is abundant, glycolysis may simply outrun the mitochondria's ability to process pyruvate.

The excess pyruvate gets converted to lactate—not because the cell prefers it, but because that's the only way to regenerate NAD+ (needed to keep glycolysis running) when the mitochondria are saturated.

This "overflow metabolism" view suggests the Warburg effect isn't always adaptive. It may sometimes be an unavoidable consequence of running glycolysis at high speed.

Both views may be partly true. Different cancers, different conditions, different explanations.

Oncogenes and Metabolism

The discovery that cancer-driving mutations directly regulate metabolism was transformative.

MYC, a famous oncogene, upregulates glycolytic enzymes and glutamine transporters. It rewires metabolism toward biosynthesis.

HIF-1α, a transcription factor activated by low oxygen (but also by oncogenic signals), turns on glycolytic genes and suppresses mitochondrial respiration.

PI3K/AKT signaling, commonly activated in cancer, stimulates glucose uptake and glycolysis.

p53, the most commonly mutated tumor suppressor, normally promotes oxidative phosphorylation. When p53 is lost, cells shift toward glycolysis.

The pattern is striking. Gain-of-function mutations in oncogenes promote glycolysis. Loss-of-function mutations in tumor suppressors also promote glycolysis. The metabolic shift isn't collateral damage—it's part of the program.

Cancer cells aren't metabolically dumb. They're metabolically reprogrammed.

The Tumor Microenvironment

Cancer doesn't happen in a vacuum. Tumors exist in complex microenvironments with diverse cell types: cancer cells, immune cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells.

The Warburg effect affects this entire ecosystem.

Acidification. Lactate production acidifies the tumor microenvironment. This low pH inhibits immune cells, promotes invasion, and selects for more aggressive cancer cells. The acidity is a weapon.

Lactate as signaling molecule. Lactate isn't just waste. It's increasingly recognized as a signaling molecule that affects immune cells, promotes angiogenesis, and stabilizes HIF-1α.

Metabolic symbiosis. Some cancer cells are highly glycolytic; others in the same tumor are more oxidative. The oxidative cells can consume lactate (produced by their glycolytic neighbors) as fuel. This is the "reverse Warburg effect"—metabolic cooperation within tumors.

Stromal cells feed cancer. Cancer-associated fibroblasts may become glycolytic, producing lactate that cancer cells then consume. The tumor reprograms its neighbors.

The Warburg effect isn't just about cancer cell metabolism. It's about how that metabolism shapes the battlefield.

PET Scans: Seeing the Warburg Effect

The clinical application of the Warburg effect is PET imaging.

Positron emission tomography (PET) with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) exploits cancer's glucose hunger. FDG is a glucose analog that gets taken up by cells but can't be fully metabolized. It accumulates in tissues with high glucose uptake—like tumors.

When you inject FDG into a patient and image them with a PET scanner, tumors light up. The Warburg effect becomes visible.

FDG-PET is now standard for staging cancers, detecting metastases, and monitoring treatment response. If a tumor shrinks on CT scan but still lights up on PET, it's probably still active. If the PET signal disappears, the metabolic activity has stopped.

This wouldn't work if cancer cells metabolized glucose normally. It's the Warburg effect—the abnormally high glycolytic rate—that creates the contrast.

A century-old observation in a biochemistry lab now guides treatment decisions for millions of cancer patients.

Targeting Cancer Metabolism

If cancer depends on altered metabolism, maybe we can target that metabolism therapeutically.

The idea is appealing. The challenge is that normal cells also need glucose. You can't simply starve the body of sugar—that would kill everything.

Several approaches are being explored:

Glycolysis inhibitors. Drugs like 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) interfere with glycolysis. In theory, this should preferentially hurt cancer cells that depend on glycolysis. In practice, toxicity has been challenging. Clinical trials have had mixed results.

Lactate dehydrogenase inhibitors. LDH converts pyruvate to lactate. Blocking this enzyme prevents cancer cells from running aerobic glycolysis. Several inhibitors are in development.

Glutamine antagonists. Many cancers are addicted to glutamine, which feeds into the citric acid cycle and biosynthetic pathways. Blocking glutamine metabolism is another approach.

Mitochondria-targeting drugs. If some cancers do rely on oxidative phosphorylation (not all cancer metabolism is glycolytic), targeting mitochondria might help. Metformin, the diabetes drug, inhibits Complex I and is being studied as a cancer therapeutic.

Diet interventions. Ketogenic diets and fasting have been proposed to "starve" tumors by reducing glucose availability. The evidence is preliminary and the mechanisms debated. Cancer cells may adapt by using ketones or other fuels.

No metabolism-targeting cancer drug has become a standard of care yet. But the field is active, and the logic is sound. Cancer metabolism is different. Difference creates opportunity.

The Mitochondrial Reality

Warburg thought mitochondria were broken in cancer. Reality is more nuanced.

Some cancers have mitochondrial mutations. Mutations in succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) cause certain tumors. Mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) drive some brain cancers and leukemias. These are genuine mitochondrial defects.

But most cancer mitochondria work. They may be underutilized, but they're functional. Many cancers can switch between glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation depending on conditions.

Mitochondria contribute to cancer beyond metabolism. They regulate apoptosis (and cancer cells evade apoptosis), generate ROS (which can promote mutations and signaling), and produce biosynthetic precursors (even if full oxidation is reduced).

The TCA cycle runs partially. Cancer cells often run a truncated citric acid cycle, exporting intermediates like citrate for lipid synthesis rather than completing the full oxidation. The mitochondria aren't doing nothing—they're doing something different.

The relationship between mitochondria and cancer is not "broken versus functional." It's "reprogrammed for different priorities."

Why Does It Matter?

The Warburg effect is not just a metabolic curiosity. It reveals something fundamental about cancer.

Cancer is not primarily a disease of uncontrolled growth. It's a disease of altered state. Cancer cells adopt a different metabolism, a different relationship with their neighbors, a different program.

The shift to aerobic glycolysis is one manifestation of that altered state. It's linked to invasiveness, immune evasion, and treatment resistance. It's selected for during tumor evolution. It's maintained by oncogenic signaling.

Understanding the Warburg effect means understanding cancer as a systemic reprogramming, not just a collection of mutations. The mutations matter because they enable the reprogramming. The metabolism matters because it sustains the new state.

Cancer is a different way of being a cell. The Warburg effect is part of what makes that way possible.

Further Reading

- Warburg, O. (1956). "On the Origin of Cancer Cells." Science. - Vander Heiden, M. G., Cantley, L. C., & Thompson, C. B. (2009). "Understanding the Warburg Effect: The Metabolic Requirements of Cell Proliferation." Science. - Liberti, M. V., & Locasale, J. W. (2016). "The Warburg Effect: How Does it Benefit Cancer Cells?" Trends in Biochemical Sciences. - Pavlova, N. N., & Thompson, C. B. (2016). "The Emerging Hallmarks of Cancer Metabolism." Cell Metabolism.

This is Part 6 of the Mitochondria Mythos series. Next: "Three-Parent Babies: Mitochondrial Replacement."

Comments ()