What Is Linear Algebra? The Mathematics of Many Dimensions

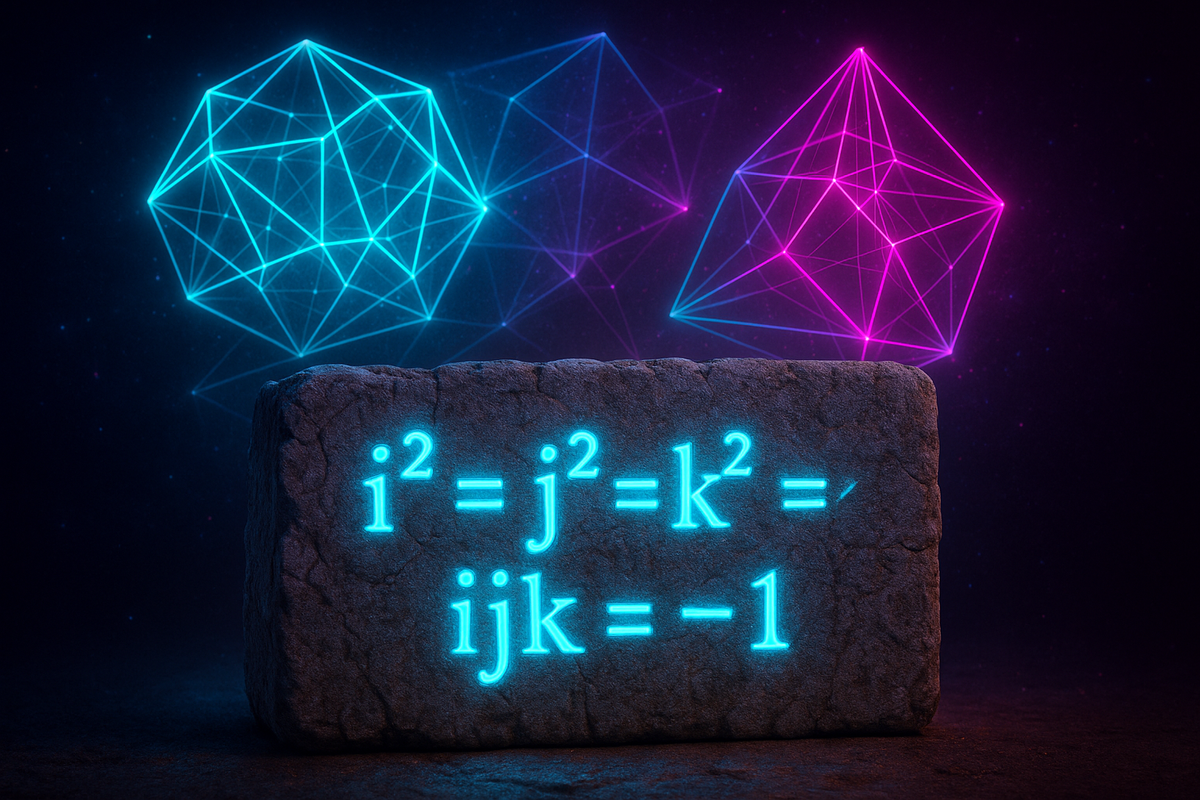

In 1843, William Rowan Hamilton was walking with his wife along the Royal Canal in Dublin when he had an insight so profound he immediately carved it into the stone of Brougham Bridge. He'd been trying to extend complex numbers into three dimensions for years. That day, he realized he needed four dimensions—and he'd just invented quaternions, the first non-commutative algebra.

Hamilton thought he'd discovered pure mathematics. What he'd actually discovered was the mathematical language needed to navigate spaceships, render video games, and train neural networks.

That's linear algebra: the mathematics of multidimensional space. And once you see it, you realize it's running everything.

The Revolution You Didn't Notice

Here's what happened while you weren't looking: linear algebra became the most practically important branch of mathematics in the modern world.

Not calculus. Not statistics. Linear algebra.

Machine learning? Linear algebra. Computer graphics? Linear algebra. Quantum mechanics? Linear algebra. Economics, signal processing, data compression, recommendation systems, computer vision—all linear algebra, all the way down.

The entire digital infrastructure of modern civilization runs on moving and transforming vectors through high-dimensional spaces. If you want to understand how anything works in the 21st century—not just use it, but understand it at the level of actual mechanism—you need linear algebra.

And yet most people graduate from high school having never encountered it.

What Linear Algebra Actually Is

At its core, linear algebra is the mathematics of vectors and matrices—quantities with direction and magnitude, and the transformations that act on them.

But that definition misses what makes it powerful.

Linear algebra is the mathematics of structure-preserving transformations. It's about understanding what stays the same when things change. It's about finding the coordinates that make complex systems simple. It's about seeing that a problem in a hundred dimensions works exactly like a problem in two dimensions, just with more numbers.

Here's the insight: most systems—physical, computational, economic—can be modeled as linear transformations. And linear transformations have elegant, computable properties.

Want to know where a particle will be after you rotate and scale your reference frame? Matrix multiplication. Want to find the principal components in a dataset with ten thousand dimensions? Eigenvalue decomposition. Want to invert a system of equations to find what inputs produce desired outputs? Matrix inversion.

Linear algebra is the toolkit for working with multidimensional systems. And everything is multidimensional once you look closely enough.

The Objects of Linear Algebra

Linear algebra has a small set of fundamental objects. Master these, and you master the field.

Vectors: The Things That Get Transformed

A vector is a list of numbers with geometric meaning.

In two dimensions: (3, 4). In three dimensions: (2, -1, 5). In a thousand dimensions: a list of a thousand numbers.

You can visualize low-dimensional vectors as arrows: the numbers tell you how far to move in each direction. Add two vectors? Put the arrows tip-to-tail. Multiply by a number? Stretch the arrow.

But vectors generalize beyond arrows. A color is a vector (red, green, blue). A song is a vector (amplitude at each frequency). A document is a vector (count of each word). Any time you have multiple related quantities, you have a vector.

The power of vectors: they let you treat complex multidimensional objects as single mathematical entities. You can add them, scale them, measure distances between them. All the geometric intuition you have from moving around in space? It generalizes.

Matrices: The Machines That Transform Vectors

A matrix is a rectangular array of numbers. But it's better to think of it as a function that eats vectors and spits out different vectors.

Feed a matrix a vector. Get a new vector back. The matrix has transformed it—rotated it, stretched it, sheared it, or collapsed it to a lower dimension.

This is the key insight: matrices encode transformations. When you multiply a vector by a matrix, you're asking "what happens to this vector when space undergoes this transformation?"

Matrix multiplication isn't arbitrary symbol-pushing. It's function composition. Applying one transformation, then another. The arithmetic rule (rows times columns) falls out of requiring that composing transformations work correctly.

Transformations: The Essence of the Whole Game

Linear algebra is fundamentally about transformations—functions from vectors to vectors that preserve addition and scaling.

If T is a linear transformation:

- T(v + w) = T(v) + T(w)

- T(cv) = cT(v)

That's it. That's what "linear" means. Lines stay lines. The origin stays put. Parallel lines stay parallel.

Why does this matter? Because preserving structure means preserving information. Linear transformations are predictable. They're invertible (often). They compose cleanly. They're computable.

Most systems aren't perfectly linear. But many systems are approximately linear near equilibrium. And linear systems are the ones we can actually solve.

Spaces: The Arenas Where Everything Lives

A vector space is any collection of objects you can add and scale, as long as the operations behave nicely.

Two-dimensional space (the plane) is a vector space. Three-dimensional space is a vector space. But so is the space of all polynomials. The space of all infinite sequences. The space of all functions from real numbers to real numbers.

Linear algebra doesn't care what the objects are. It cares whether you can add them and multiply by scalars. If yes, all the machinery applies.

This abstraction is what makes linear algebra so powerful. The same theorems that work for three-dimensional space work for the space of solutions to a differential equation. Understanding vectors as arrows helps build intuition. Understanding vector spaces as abstract structures lets you apply that intuition everywhere.

Why Linear Algebra Works

Here's the deep reason linear algebra dominates modern mathematics and science: linearity is the first-order approximation of everything.

Near any point, any smooth function looks linear. The derivative—calculus's central object—is a linear approximation. When you zoom in on a curve, it looks like a line. When you zoom in on a curved surface, it looks like a plane.

This means you can use linear algebra to understand nonlinear systems. Not exactly, but approximately. And often, the approximate answer is all you need.

Machine learning works by stacking thousands of linear transformations separated by nonlinearities. Neural networks are linear algebra plus a little bit of nonlinearity, iterated. The linearity makes it trainable. The nonlinearity makes it expressive.

Computer graphics works by representing objects as meshes of flat polygons, then transforming them with matrices. The world is curved. We approximate it with flat pieces and linear transformations.

Physics works by linearizing equations near equilibrium. The universe is nonlinear. But most of the time, most systems stay close to equilibrium, where linear approximations hold.

Linear algebra is the mathematics of "close enough." And close enough is usually good enough.

What Makes It Different from Other Math

You've learned arithmetic: how to manipulate numbers.

You've learned algebra: how to manipulate symbols representing numbers.

You've learned geometry: how to reason about shapes and space.

You've learned calculus: how to handle change and accumulation.

Linear algebra synthesizes all of this. It's algebraic manipulation of geometric objects undergoing transformation, with calculus lurking in the background whenever you take limits or approximations.

But it has its own character:

It's computational. Linear algebra problems reduce to algorithms. You're not proving existence theorems (mostly). You're computing actual answers. Matrices multiply. Equations solve. Eigenvalues calculate.

It's visual. Low-dimensional linear algebra has gorgeous geometric interpretation. You can see what's happening. A matrix is a transformation of space. An eigenvalue is a scaling factor along a special direction. A determinant is a volume-scaling factor.

It's scalable. The same operations that work in two dimensions work in two million dimensions. Your intuition comes from low dimensions. Your applications live in high dimensions. But the mathematics is the same.

It's foundational. Linear algebra is the substrate on which huge amounts of modern mathematics and science are built. Functional analysis, differential equations, quantum mechanics, machine learning—all build on linear algebra.

The Tools You'll Master

This series will take you through the core toolkit:

Vectors and matrices: The basic objects. How to add, multiply, and transform them. What they represent geometrically.

Matrix multiplication: Why it works the way it does. How it represents composition of transformations. Why the rule is row-times-column.

Determinants: How to measure volume scaling. What it means when a determinant is zero. How determinants relate to invertibility.

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors: The directions that survive transformation unchanged. Why they matter. How to compute them. What they reveal about the transformation.

Systems of linear equations: How matrices encode equation systems. How to solve them using row reduction. When solutions exist and when they don't.

Vector spaces: The abstract structures that generalize geometric space. Subspaces, span, linear independence. The language of mathematical structure.

Linear transformations: Functions that preserve structure. How they relate to matrices. The kernel and image. Rank and nullity.

Basis and dimension: How to give coordinates to abstract spaces. What dimension actually measures. How to change coordinates.

Applications: Where linear algebra appears in the real world. Machine learning, computer graphics, quantum mechanics, economics.

Why Now

Linear algebra used to be a niche topic—something engineers learned, mathematicians studied abstractly, and everyone else ignored.

Then computers happened.

Computers are exceptionally good at one thing: doing arithmetic on large arrays of numbers. That's literally what matrix multiplication is. The thing computers are built to do is the thing linear algebra formalizes.

Then machine learning happened.

Neural networks are linear algebra. Not metaphorically—literally. Layers of matrix multiplications with nonlinear activation functions. Training a neural network is solving a giant optimization problem in high-dimensional space using linear algebra.

Then data happened.

Modern datasets have thousands or millions of dimensions. Every customer is a vector of purchasing behaviors. Every image is a vector of pixel values. Every document is a vector in word-frequency space. Understanding high-dimensional data requires linear algebra.

We're living in the linear algebra century. The mathematics that Hamilton carved into a bridge 180 years ago is now running the machine learning models, graphics engines, and recommendation systems that structure daily life.

If you want to understand the infrastructure of modernity, you need to understand linear algebra.

What To Expect

This series builds from concrete to abstract. We'll start with vectors you can visualize, matrices you can see as transformations, and operations you can do by hand.

Then we'll generalize. You'll see that the patterns that work in two dimensions work in two hundred dimensions. That the geometric intuition applies to abstract spaces. That the computational techniques scale.

We'll emphasize intuition over formalism. Proofs will appear when they illuminate. Calculations will appear when they clarify. But the goal is understanding, not procedure.

You'll learn to see problems in terms of linear structure. To recognize when linear algebra applies. To translate between geometric, algebraic, and computational perspectives.

By the end, you won't just know how to multiply matrices. You'll understand why matrices multiply the way they do. You'll see them as transformations, not arrays. You'll think in terms of spaces and maps and structure-preservation.

You'll speak the language that underlies machine learning, quantum mechanics, and computer graphics. You'll understand the mathematics that runs the modern world.

Linear algebra is the mathematics of structure. Let's learn to see structure.

This is Part 1 of the Linear Algebra series, exploring the mathematics of vectors, matrices, and transformations. Next: "Vectors: Quantities with Direction and Magnitude."

Part 1 of the Linear Algebra series.

Previous: Linear Algebra Explained Next: Vectors: Quantities with Direction and Magnitude

Comments ()