What Is Vector Calculus? The Mathematics of Fields

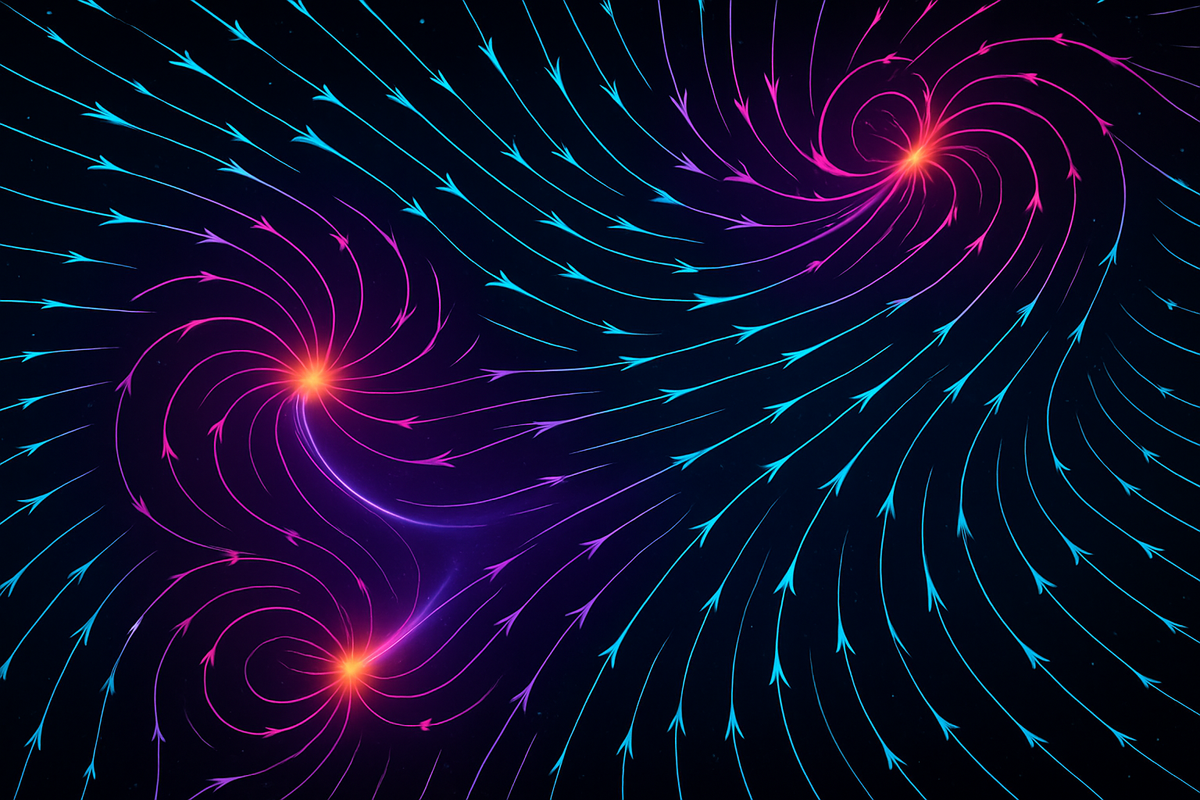

Vector calculus is what happens when you take the machinery of calculus—derivatives, integrals, the fundamental theorem—and extend it to vector fields. It's the mathematical language for describing anything that has both magnitude and direction at every point in space. Wind speed. Electric fields. Fluid flow. Gravitational pull. Heat flux. Anything where the answer to "what's happening here?" is a vector, not just a number.

In regular calculus, you work with scalar fields: functions that map points to numbers. Temperature is a scalar field—every point in your room has a temperature value. In vector calculus, you work with vector fields: functions that map points to vectors. Air velocity is a vector field—every point in your room has both a speed and a direction of airflow.

This shift from scalars to vectors doesn't just add complexity. It fundamentally changes what kinds of questions you can ask and what kinds of structures emerge in the mathematics.

The Core Machinery

Vector calculus gives you three new differential operators beyond the basic derivative:

Gradient takes a scalar field and produces a vector field. It points in the direction of steepest increase. If you have a temperature distribution, the gradient tells you which way is "uphill" in temperature space and how steep that climb is.

Divergence takes a vector field and produces a scalar field. It measures how much the field is spreading out or converging at each point. If you have fluid flow, divergence tells you where fluid is being created (sources) or destroyed (sinks).

Curl takes a vector field and produces another vector field. It measures rotation—how much and around which axis the field swirls at each point. If you have fluid flow again, curl tells you where the fluid is spinning and in what direction.

These three operators are related through a single symbol: ∇ (nabla or "del"), which acts like a vector of partial derivatives. Gradient is del acting on a scalar. Divergence is del dotted with a vector. Curl is del crossed with a vector. The del operator unifies the entire framework.

Integration in Vector Calculus

In single-variable calculus, you integrate over intervals. In multivariable calculus, you integrate over regions. In vector calculus, you integrate over curves and surfaces embedded in vector fields.

Line integrals integrate a vector field along a curve. They answer questions like "how much work does this force field do on a particle moving along this path?" You're summing up tiny dot products of the field with the path direction at each point.

Surface integrals integrate a vector field over a surface. They answer questions like "how much fluid flows through this surface per unit time?" You're summing up tiny dot products of the field with the surface normal at each point. This is called flux.

These aren't just generalizations for generalization's sake. Line integrals and surface integrals are the natural tools for calculating work, circulation, flux, and flow—quantities that appear everywhere in physics and engineering.

The Three Great Theorems

Regular calculus has the fundamental theorem: the integral of a derivative equals the difference in values at the endpoints. Vector calculus has three fundamental theorems, each connecting a local property (described by a differential operator) to a global property (described by an integral).

Green's Theorem works in two dimensions. It says the line integral around a closed curve equals the double integral of curl over the region inside. Local rotation sums to global circulation.

Stokes' Theorem generalizes Green's to three dimensions. It says the line integral around the boundary of a surface equals the surface integral of curl over that surface. It's the fundamental theorem for curl.

The Divergence Theorem (also called Gauss's Theorem) says the surface integral of a vector field over a closed surface equals the volume integral of divergence inside. It's the fundamental theorem for divergence. What flows out of a region equals what's being created inside.

These three theorems aren't separate results—they're all instances of the same deep structure. They connect boundary behavior to interior behavior. They let you transform hard integrals into easier ones. They reveal conservation laws. They're the reason vector calculus works as a unified system rather than a collection of tricks.

Why This Matters: Maxwell's Equations

Here's the kicker: almost every fundamental law of physics is naturally expressed in vector calculus.

Take electromagnetism. Before Maxwell, there were separate laws for electricity and magnetism, described with verbose paragraphs of verbal reasoning. Maxwell reformulated everything in terms of vector fields and differential operators:

∇ · E = ρ/ε₀ (Gauss's law: electric charge creates diverging electric field) ∇ · B = 0 (no magnetic monopoles: magnetic field has no divergence) ∇ × E = -∂B/∂t (Faraday's law: changing magnetic field creates curling electric field) ∇ × B = μ₀J + μ₀ε₀∂E/∂t (Ampère-Maxwell law: current and changing electric field create curling magnetic field)

These four equations completely describe classical electromagnetism. They're compact, they're beautiful, and they only make sense with vector calculus. The divergence and curl operators aren't arbitrary—they're capturing the actual physical structure of how fields behave.

Fluid dynamics works the same way. The Navier-Stokes equations describe fluid motion using divergence, curl, and gradient. General relativity extends these ideas to curved spacetime. Quantum field theory uses even more sophisticated versions.

If you want to understand how physicists think about the world at a fundamental level, you need vector calculus. It's not a tool they happened to choose—it's the language the universe seems to speak.

The Geometric Intuition

Here's what makes vector calculus different from the abstract symbolic manipulation it often appears to be in textbooks: every operator and every theorem has a clear geometric meaning.

Gradient points uphill. It's geometric.

Divergence measures expansion. Put a tiny box around a point. If divergence is positive, more flows out than in—the box is a source. If divergence is negative, more flows in than out—the box is a sink. It's geometric.

Curl measures circulation. Put a tiny paddle wheel at a point. If curl is nonzero, the field will make it spin. The direction of the curl vector tells you the axis of rotation. It's geometric.

The theorems are geometric too. Green's Theorem says if you have a bunch of tiny whirlpools inside a region, their combined circulation equals the circulation around the boundary. Stokes' Theorem extends this to curved surfaces in 3D. The Divergence Theorem says if you have sources and sinks in a volume, the total creation equals the net flow out.

This geometric intuition is why vector calculus is teachable at all. You're not just manipulating symbols—you're describing real spatial relationships. The mathematics mirrors the physics, which mirrors our geometric intuition about space.

What Makes It Hard (And Why It's Worth It)

Vector calculus has a reputation for being difficult, and some of that is deserved. There are three main sources of cognitive load:

Notation density. Between del, cross products, dot products, partial derivatives, multiple integrals, and coordinate systems, there's a lot of symbolic machinery to track. The notation can obscure the geometric meaning if you're not careful.

Coordinate system dependence. Many computations require choosing a coordinate system (Cartesian, cylindrical, spherical), and the same geometric object looks very different in different coordinates. This is genuinely confusing.

Integration complexity. Setting up surface integrals and volume integrals requires spatial reasoning about parameterizations and bounds that goes beyond anything in single-variable calculus.

But here's the thing: once it clicks, it stays clicked. Vector calculus is one of those domains where the initial barrier is high but the plateau afterward is stable. You develop intuition for how fields behave, how operators transform them, and how theorems connect different representations. And that intuition transfers everywhere.

After you understand divergence, you'll never look at fluid flow the same way. After you understand curl, rotating fields make geometric sense. After you internalize the fundamental theorems, you'll see conservation laws and symmetries everywhere in physics.

The Historical Context

Vector calculus as we know it today was developed in the late 19th century, primarily by Josiah Willard Gibbs and Oliver Heaviside. They were trying to make Maxwell's electromagnetic theory usable for working physicists and engineers.

Before their work, Maxwell's original formulation used quaternions—a different mathematical framework that was powerful but cumbersome. Gibbs and Heaviside stripped out the quaternion scaffolding and reformulated everything in terms of vectors, dot products, cross products, and the differential operators we use today.

This wasn't just a notational improvement. It was a conceptual clarification. By separating scalar and vector quantities, by introducing clear notation for gradient, divergence, and curl, they made the geometric structure of the theory visible. The mathematics became a tool for thought rather than an obstacle to understanding.

There's an ongoing debate about whether we lost something by abandoning quaternions (and their modern generalization, geometric algebra). Some argue that the cross product is an inelegant hack and that geometric algebra provides a more unified framework. Maybe. But vector calculus in its current form has proven extraordinarily productive for over a century, and it remains the standard language for physics and engineering.

Where It Goes From Here

Vector calculus is not the end of the story. It's a stepping stone.

Tensor calculus generalizes vectors to tensors—objects that transform predictably under coordinate changes. General relativity requires tensor calculus because spacetime curvature is described by tensors. Stress and strain in materials are tensors. Anything with multiple indices generally requires tensor machinery.

Differential forms provide an alternative framework that's coordinate-independent from the start. Forms make many theorems cleaner and reveal deep connections to topology. If you study differential geometry or mathematical physics, you'll encounter differential forms as the "right" language for integration and the fundamental theorems.

Geometric algebra subsumes vector calculus into a more unified algebraic framework where dot products and cross products emerge as special cases of a single product. Some physicists advocate for teaching geometric algebra instead of traditional vector calculus.

But for understanding classical electromagnetism, fluid dynamics, and most of engineering physics, standard vector calculus is still the most practical tool. It's what working scientists use. It's what appears in textbooks. It's what you need to know.

The Conceptual Shifts Required

Learning vector calculus requires upgrading your mathematical intuition in several ways:

From functions to fields. Stop thinking of functions as graphs. Start thinking of them as assignments of values to space. A vector field is "the wind" or "the current"—something that exists everywhere and has local structure.

From curves to paths of integration. In single-variable calculus, you integrate over intervals on the x-axis. In vector calculus, you integrate over curves that wind through space, or surfaces that bend and twist. The geometry of the path matters.

From derivatives to operators. The derivative ∂/∂x is an operator—a machine that takes functions to functions. Del is a vector-valued operator. Divergence, gradient, and curl are all operators built from del. You're manipulating these machines, not just numbers.

From local to global. The fundamental theorems connect infinitesimal local properties (what's happening at a point) to finite global properties (what's happening over a region). This local-to-global thinking is central to all of modern analysis.

These shifts are subtle but profound. They require reconceptualizing what calculus is about. It's not about finding areas under curves—it's about understanding how local differential structure determines global integral behavior. That's a big conceptual leap.

Practical Applications

Why do engineers care about vector calculus? Because it's directly applicable to real-world design problems:

Fluid dynamics: Airflow over a wing, water flow through a pipe, ocean currents—all described by vector fields and analyzed using divergence and curl.

Electromagnetics: Antenna design, circuit theory, radio wave propagation—all grounded in Maxwell's equations, which are pure vector calculus.

Heat transfer: Temperature gradients drive heat flow. Divergence tells you where heat is accumulating. This is essential for thermal engineering.

Mechanics: Stress and strain tensors describe how materials deform under load. Force fields determine motion. Work and energy calculations use line integrals.

Computer graphics: Rendering realistic light requires integrating radiance over surfaces. Simulating cloth or fluid requires solving vector field equations. Vector calculus is embedded in the physics engines of video games and animation software.

If you build anything that moves, flows, flexes, heats, or radiates, you need vector calculus. It's not abstract theory—it's the working language of physical design.

The Structure Ahead

This series will walk through vector calculus systematically:

First, we'll establish vector fields as the objects of study—what they are, how to visualize them, what physical phenomena they represent.

Then we'll cover the integration tools: line integrals for work and circulation, surface integrals for flux.

Next, the differential operators: divergence, curl, and gradient, unified under the del operator.

Finally, the fundamental theorems: Green's Theorem, Stokes' Theorem, and the Divergence Theorem, showing how they connect local and global properties.

We'll conclude with Maxwell's equations as the synthesis—the place where all these tools come together to describe a unified physical theory.

By the end, you'll understand not just how to compute with vector calculus, but why it's structured the way it is and what it reveals about the geometry of space and the behavior of fields.

Vector calculus is one of those rare mathematical frameworks that's both theoretically elegant and practically indispensable. It's worth the effort to learn it properly—not as a collection of formulas to memorize, but as a coherent system for reasoning about the physical world.

Let's get started.

Part 1 of the Vector Calculus series.

Previous: Vector Calculus Explained Next: Vector Fields: Arrows at Every Point

Comments ()