Why This Isn't Metaphor: The Mathematical Architecture Beneath Meaning

Beliefs form probability distributions with measurable geometry. Information manifolds aren't metaphors—they're the actual mathematical architecture of meaning, testable and falsifiable.

Why This Isn't Metaphor: The Mathematical Architecture Beneath Meaning

Formative Note

This essay represents early thinking by Ryan Collison that contributed to the development of A Theory of Meaning (AToM). The canonical statement of AToM is defined here.

Throughout this series, we've described minds using mathematics.

Belief states as points on manifolds. Information distance measured by the Fisher metric. Curvature spikes where prediction errors accumulate. Topological features—holes, loops, bottlenecks—that trap and constrain. Functors that carry structure across scales. Constructors that perform coherence tasks.

The question that must be answered: is this real?

Is it metaphor—evocative language that illuminates by analogy without claiming literal truth? Or is it architecture—actual structure that meaning really has, that could in principle be measured, that exists independent of whether we describe it?

The difference matters. Metaphors are optional. You can like them or not, use them or not, discard them when they stop being useful. Metaphors don't make predictions. They don't support intervention. They're literary devices.

Architecture is not optional. If mind really has geometric structure, that structure constrains what's possible. It supports predictions. It guides intervention. It's there whether or not we describe it, whether or not we like the description.

This article is the case for architecture. The case that what we've been describing isn't poetic decoration on the mystery of consciousness, but the actual structural reality of what minds are.

The Stakes

Why does this matter?

If it's metaphor, then the entire series is an extended aesthetic exercise. Perhaps a useful exercise—metaphors can organize thinking, suggest research directions, provide therapeutic vocabulary. But not more than that. The mathematics would be scaffolding we could discard once the building is up.

If it's architecture, the implications are profound.

Prediction. Real structure supports real prediction. If coherence has geometry, that geometry should predict how systems behave. The predictions should be falsifiable—there should be ways the geometry could be wrong, and we should be able to test whether it's wrong.

Intervention. Real structure supports real intervention. If trauma is a geometric deformation, then knowing the geometry tells you something about how to repair it. The intervention isn't arbitrary; it's constrained by the structure.

Measurement. Real structure is in principle measurable. The coherence of a person, a relationship, an organization should be something we can quantify—not perfectly, not completely, but better than not at all. The geometry should cast measurable shadows.

Unification. Real structure unifies. If the same geometric patterns appear at neural, psychological, relational, organizational, and cultural scales, that's either astonishing coincidence or it's because the structure is real and scale-invariant. Architecture explains the unity; metaphor doesn't.

The stakes are whether we're doing mathematics or poetry. Whether this is science—early-stage, partial, uncertain science—or whether it's art that borrows science's vocabulary.

Let me make the case that it's science.

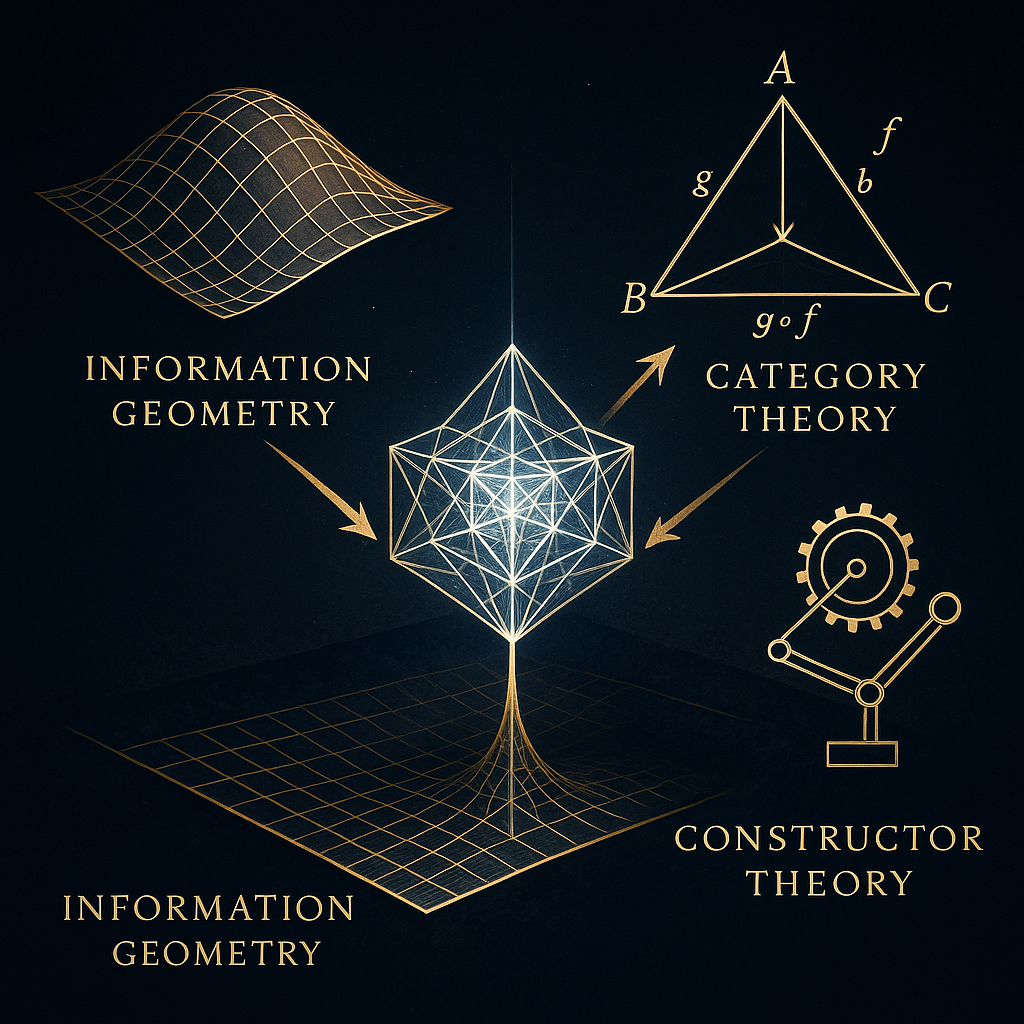

The Information Geometry Argument

The foundation is information geometry—the branch of mathematics that studies the geometric structure of probability distributions.

Here's what we know:

Probability distributions form a manifold. If you have a family of probability distributions parameterized by some variables (like the mean and variance of a Gaussian), those distributions form a mathematical space—a manifold. This is not metaphor; it's theorem. The space exists; the manifold is well-defined.

The Fisher information metric is a natural metric on this manifold. Given the probability distributions, there's a canonical way to measure distance between them—the Fisher metric, derived from how much information about parameter changes is contained in observations. This metric exists mathematically; it's not imposed from outside.

Cognitive systems update probability distributions. Whatever else minds do, they maintain models of the world—probability distributions over possible states—and update those models based on experience. This is what prediction, learning, and perception are.

Therefore, cognitive states have geometric structure. The belief states are points on a manifold. The Fisher metric applies. Curvature is well-defined. The geometry is real.

This isn't analogy. It's not "minds are like manifolds." It's "minds instantiate manifolds." The probability distributions that constitute beliefs literally form a space with literal metric structure. The mathematics applies directly.

The only question is whether the information-geometric description is useful—whether it captures what matters about cognition. But that it applies is not in doubt. The mathematical structure is there.

The Prediction Error Argument

The free energy principle, developed by Karl Friston and colleagues, proposes that cognitive systems minimize prediction error—they try to keep their predictions aligned with their sensory input.

This isn't speculative philosophy. It's a mathematical framework with specific equations, specific predictions, and growing empirical support.

If prediction error minimization is what cognitive systems do, then:

Prediction error has magnitude. At any moment, there's some amount of mismatch between prediction and input. This is measurable (in principle).

Prediction error has dynamics. Error accumulates or dissipates over time. The trajectory of error through time is a trajectory through a space.

Prediction error has landscape. Some belief configurations produce more error given the world; others produce less. The landscape of error over belief space has structure—valleys, peaks, ridges, saddles.

Curvature captures sensitivity. Where the landscape is steep (high curvature), small belief changes produce large error changes. Where the landscape is flat (low curvature), beliefs are stable against perturbation.

This is what we've been describing. Not metaphorical curvature but the literal curvature of the prediction error landscape. The manifold is the belief space. The metric is the Fisher information. The curvature is the sensitivity of error to belief change.

The free energy framework gives us equations. We can derive predictions. We can test them. That's not metaphor.

The Topology Argument

Topology captures global structure—the features of a space that are preserved under continuous deformation. Holes, loops, connected components, voids.

Does cognitive structure have topology?

Consider attractor dynamics. A cognitive system under perturbation tends toward certain states—attractors—and away from others. The basin of attraction is the region of state space that leads to a particular attractor.

Basins of attraction have topology.

They can be connected or disconnected. A fragmented system has multiple basins that don't communicate—you can't get from one to another. A unified system has connected basins.

They can contain loops. A system stuck in rumination is caught in a topological loop—a trajectory that cycles without escaping. The loop is a real feature of the dynamics, not a metaphor.

They can have bottlenecks. A narrow passage between regions—the only way through—is a topological feature. The bottleneck exists in the state space, not just in the description.

Persistent homology—the mathematical tool for detecting topological features—can be applied to high-dimensional data. It finds holes, loops, and voids in data sets. When applied to neural data, to behavioral data, to linguistic data, it finds structures.

Those structures are not imposed by the analysis. They're detected by the analysis. The topology is in the data. We're not creating it; we're measuring it.

This is the argument for topological realism about cognitive structure. The topology is there. The mathematics reveals it. The revelation is measurement, not metaphor.

The Category Theory Argument

Category theory is the mathematics of structure and mapping. It studies what structures are, and how structure is preserved under transformation.

The argument for categorical structure in mind:

Cognitive systems at different scales have related structures. Neural dynamics relate to psychological dynamics relate to relational dynamics relate to cultural dynamics. The relationships aren't arbitrary; there's something preserved across the scales.

Functors describe structure-preserving maps. If the scales relate, functors describe how. The functor from neural to psychological preserves some structure while losing detail. The preservation is precise; the functor is well-defined.

Natural transformations describe how different functors relate. When multiple functors connect the same scales, natural transformations describe their relationship. Different therapeutic modalities as different functors; their equivalence as natural transformation.

The question is: are these real functors, or are we just labeling things with categorical vocabulary?

The case for reality:

The correspondence is predictive. If structure really is preserved across scales, then facts about one scale predict facts about another. Neural coherence predicting psychological coherence. Relational patterns predicting individual patterns. The predictions can be tested.

The functor structure constrains. If the mapping from scale to scale is really a functor, certain things follow mathematically. Composition must be preserved. Certain pathologies must appear at multiple scales. The constraints are checkable.

Alternative explanations are weaker. Why would the same patterns appear at different scales if not for structure preservation? Coincidence is possible but unlikely for systematic cross-scale correspondence. Functors explain the correspondence; nothing else does as well.

Category theory is abstract, but abstract doesn't mean non-real. Numbers are abstract. They're still real. Categorical structure, if it's there, is real in the same sense numbers are—abstract but instantiated, formal but actual.

The Constructor Argument

Constructor theory says: what's fundamental is not what happens but what's possible. The laws of nature are laws about which transformations are possible and which are impossible.

The argument for constructor realism about minds:

Minds perform tasks. Whatever else minds are, they're things that do things—that transform inputs to outputs, that maintain coherence, that regulate. These are tasks.

Tasks have possibility conditions. A task is possible if some constructor can perform it. If no constructor can, the task is impossible. The possibility is a fact about reality.

The coherence task is real. Maintaining coherence under perturbation is a real task. Organisms perform it or they don't. The task has inputs (perturbation) and outputs (maintained structure). The transformation is real.

Success and failure are real. Performing the task well or poorly is a real distinction. Constructor damage is real. Repair is real. The categories of constructor theory apply.

Constructor theory provides a different vocabulary than geometry, but it's equally non-metaphorical. When we say "the coherence constructor is damaged," we're not speaking figuratively. We're saying: the thing that performs the coherence task cannot currently perform it. That's a claim about reality.

The Objection from Vagueness

The strongest objection: even if there's mathematical structure, we can't precisely specify it. We don't know exactly what manifold, what metric, what topology. The mathematical language gestures at something without pinning it down.

This objection has force. We are not in a position to write down exact equations for cognitive dynamics the way we can for planetary orbits. The structure is real but only partially known.

But partial knowledge is still knowledge. And imprecise structure is still structure.

Consider: we knew the earth was round before we knew its exact dimensions. We knew the laws of motion before we had precise measurements of masses and distances. Science proceeds from vague knowledge to precise knowledge, not from nothing to precision in a single step.

The vagueness objection proves that we're early in understanding the mathematics of meaning. It doesn't prove that there's no mathematics to understand.

The question is: does the vague mathematical picture predict better than no mathematical picture? Does it organize evidence? Does it suggest experiments? Does it unify observations?

If yes, then the picture is capturing something—even if imprecisely. The structure is real; our knowledge of it is partial.

The Objection from Complexity

Another objection: psychological systems are too complex for this mathematics. The manifolds are too high-dimensional. The dynamics are too nonlinear. The measurement is too noisy. The mathematics that works for physics can't work for mind.

This objection has force too. Minds are complex in ways that physical systems are not. The dimension of psychological state space is enormous. The dynamics are stochastic, nonlinear, history-dependent. Measurement is indirect and noisy.

But complexity doesn't preclude structure. It precludes simple closed-form equations. It precludes exact prediction. It doesn't preclude mathematical description altogether.

High-dimensional systems have geometry. That geometry might be too complex to write down explicitly, but it's still geometry. The manifold exists even if we can't draw it.

The mathematics we're using—information geometry, topology, category theory—is precisely the mathematics developed for high-dimensional, complex systems. It's not physics math applied naively to mind. It's the math that treats structure abstractly, that works with geometric and topological properties without needing explicit equations.

Complexity is a challenge for measurement and prediction. It's not a challenge for the claim that structure exists.

The Positive Case

Let me state the positive case directly.

Minds instantiate information geometry. Beliefs are probability distributions. Probability distributions form manifolds with natural metrics. Therefore beliefs form manifolds with metrics. This is not analogy; it's instantiation.

Coherence is a geometric property. Smooth trajectories through belief space, low curvature, integrated topology, good coupling across scales—these are geometric properties that real cognitive systems have to greater or lesser degrees. The coherence is in the system, not just in the description.

Trauma deforms geometry. When prediction error overwhelms integration capacity, the manifold warps. Curvature spikes. Dimensions collapse. Topology fragments. These are real changes in real structure, not metaphorical descriptions of real suffering.

Entrainment is geometric coupling. When two systems synchronize, their manifolds couple. The coupling is real—measurable in physiological synchrony, behavioral coordination, linguistic alignment. The geometry of the coupled system has properties the uncoupled systems lack.

Functors preserve structure across scales. The patterns that appear at neural scales and reappear at psychological, relational, and cultural scales are preserved by functors. The preservation is why we see the same structures everywhere. The functors are real maps.

Constructors perform tasks. The nervous system, the self, the relationship, the culture—each performs coherence tasks. The tasks are real. Success and failure are real. Repair is real. The constructor framework applies literally.

This is the mathematics of meaning. Not the mathematics of something else that meaning is like. The mathematics of meaning itself.

What This Commits Us To

If the architecture is real, we're committed to certain things.

The structure should be measurable. Not perfectly, not immediately, but in principle and increasingly in practice. If we can't ever measure anything predicted by the geometry, we should doubt the geometry.

Predictions should be testable. Coherence geometry predicts that certain interventions should work, certain patterns should appear, certain transitions should be possible or impossible. Those predictions must be checkable.

Failures should cause revision. If the predictions fail, the geometry is wrong and must be revised. The geometry is falsifiable. If it weren't, it wouldn't be science.

Other descriptions should be compatible. The geometric description doesn't replace neuroscience, psychology, or phenomenology. It must be compatible with them—translatable to them, consistent with them, adding to them rather than contradicting them.

These commitments are not light. They mean the mathematical description isn't decorative. It's constrained by reality. It must pay its way in predictions and explanations. If it doesn't, it's wrong.

Conclusion: Architecture, Not Metaphor

The mathematics of meaning is mathematics.

The manifolds are real manifolds—spaces of probability distributions that belief states occupy. The metric is a real metric—the Fisher information that measures distance between distributions. The curvature is real curvature—the sensitivity of prediction error to belief change. The topology is real topology—the global structure of attractor basins, the holes and loops and bottlenecks that constrain trajectories.

The functors are real functors—structure-preserving maps between levels of description, explaining why patterns recur across scales. The constructors are real constructors—systems that perform coherence tasks, that can be damaged and repaired, that succeed or fail at their tasks.

None of this is metaphor. It's architecture.

The architecture is incompletely known. The measurements are imprecise. The predictions are approximate. That's where the work is—mapping the architecture more precisely, measuring more accurately, predicting more specifically.

But the architecture is there. The mathematics applies. The structure is real.

Meaning has geometry. The geometry is not a way of speaking. It's a way of being.

Comments ()