Xenobots: Living Robots Made from Cells

In 2020, a team of researchers created something that didn't quite fit existing categories.

They took cells from frog embryos—specifically, skin cells and heart cells from Xenopus laevis, the African clawed frog—and arranged them into tiny blobs, about half a millimeter wide. The blobs weren't frogs. They weren't random cell clumps. They were designed shapes, assembled according to computer simulations.

And they moved.

The heart cells contracted rhythmically, propelling the blobs through water. The skin cells provided structure. The little machines could navigate their environment, push small particles around, and even heal themselves when damaged.

The researchers called them xenobots—after the frog species, plus "robot." But robot felt wrong. These weren't metal and silicon. They were living tissue. They were biological.

Xenobots were something new: living robots that weren't evolved by nature or designed by traditional engineering. They were computationally designed and biologically constructed.

We built machines from living cells. And they did things we didn't fully predict.

How to Build a Xenobot

The process has two parts: computational design and biological construction.

Design: The team used an evolutionary algorithm on a computer. They simulated small arrangements of cells and tested whether they could move. Skin cells were passive—they provided structure. Heart cells contracted rhythmically—they provided propulsion.

The algorithm evolved shapes that could convert heart cell contractions into forward motion. After many simulated generations, promising designs emerged: asymmetric blobs where coordinated contractions would push in one direction.

This is digital evolution—using computers to explore design space before building anything. The computer doesn't understand why a shape works; it just tests which shapes perform better and evolves toward them.

Construction: The researchers took actual frog embryo cells—dissecting them from early-stage embryos—and shaped them by hand (using tiny forceps and tools) according to the computer's designs. The cells stuck together and self-organized to some degree, but the initial shape was human-crafted.

Once assembled, the xenobots lived for days or weeks, moving around their dishes, doing what their structure dictated.

The design is computational. The construction is biological. The result is hybrid.

What Xenobots Can Do

Xenobots are tiny—smaller than a pinhead—but surprisingly capable.

Locomotion. The heart cells contract spontaneously, with a natural rhythm. The asymmetric shape converts this into movement. Xenobots can "walk" through water using wave-like contractions.

Object manipulation. Groups of xenobots can push small particles into piles. This is emergent behavior—they weren't explicitly programmed to do it, but their movements combined with the environment produce it.

Self-healing. Cut a xenobot in half, and it can repair itself. The cells reorganize. The machine keeps working. This is one of the most striking features—try cutting a metal robot and see if it self-heals.

Cooperation. Multiple xenobots can work together, inadvertently or by design. Their collective behavior can accomplish tasks that individuals can't.

No predetermined plan. Xenobots don't have DNA telling them to be a frog. They don't have a nervous system deciding what to do. Their behavior emerges from the physics of their structure and the contractile properties of heart cells. It's mechanical, but it's also living.

Self-Replicating Xenobots

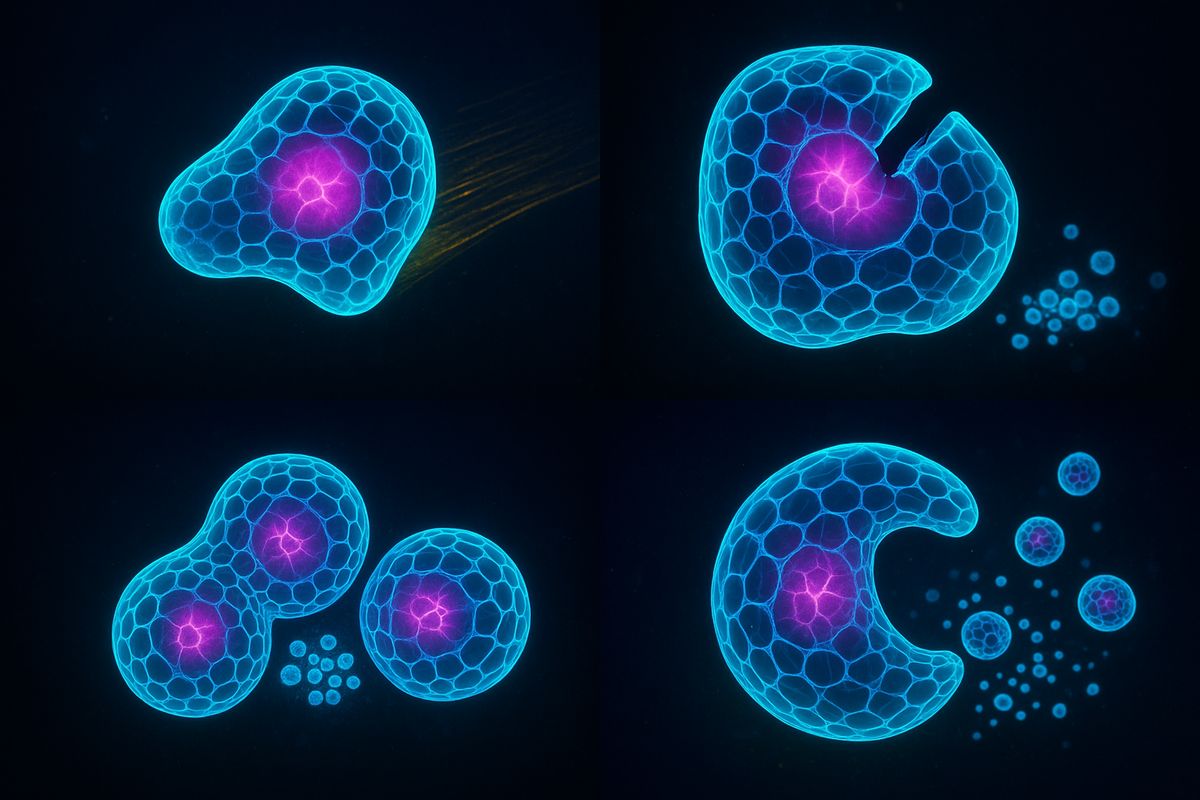

In 2021, the team announced something stranger: the xenobots could replicate.

Not like cells divide. Not like organisms reproduce. A new kind of replication, never before seen in nature.

Here's what happened: when xenobots were placed in an environment with loose frog cells, they would push cells together into piles. If the pile was the right shape, it would eventually become a new xenobot. The original xenobot had "assembled" its offspring from available parts.

This is kinematic self-replication—reproduction through movement and assembly, not through growth from within. The xenobot doesn't grow a copy inside itself; it builds a copy externally from ambient material.

The researchers used the evolutionary algorithm to optimize this. They found that C-shaped xenobots were best at piling cells in ways that produced viable offspring. The computer discovered a shape that nature never evolved.

Living machines that reproduce—not by DNA, but by construction.

What Are They, Exactly?

Xenobots challenge categories.

Are they robots? They're designed for a function and execute it autonomously. But they're made of living tissue.

Are they organisms? They're made of cells, they metabolize, they can heal. But they weren't born, don't have a genome that specifies their structure, and don't descend from a reproducing lineage.

Are they synthetic life? The cells are natural frog cells, not synthetic. The design is novel, but the components are biological.

Some researchers have called them "living machines." Others call them "biobots" or "artificial life-forms." The terminology is unsettled because the phenomenon is genuinely new.

Xenobots are not life as we know it. They're not robots as we know them. They're something in between—or something else entirely.

The Plasticity of Life

Here's what xenobots reveal about biology: cells are much more versatile than their usual roles suggest.

In a frog embryo, skin cells become skin. Heart cells become heart. Each cell type has a destiny determined by its genetic program and the signals it receives during development. The frog body plan is encoded in DNA and executed through development.

But take those same cells out of context, put them in a different arrangement, and they do something else. The skin cells become structure for a tiny machine. The heart cells become propulsion. The "program" of becoming a frog doesn't run because the context isn't there.

This is plasticity—the ability of cells to adopt different behaviors depending on their environment. The genome encodes possibilities, not inevitabilities. What actually happens depends on context.

Xenobots demonstrate that the space of possible living configurations is much larger than the space of evolved organisms. Nature discovered frogs, but nature didn't discover xenobots. They were waiting in the space of possibilities, accessible once we thought to look.

Evolution explores a tiny fraction of the possible. Design can explore more.

The Design Discovery

The xenobot project illustrates a new paradigm: computational design of living systems.

The evolutionary algorithm explored millions of possible cell arrangements, far more than humans could intuit. It discovered shapes that work—C-shapes for replication, asymmetric blobs for locomotion—that no one would have guessed.

This is the same principle as directed evolution of enzymes, but applied to whole-organism morphology. Don't design by understanding; design by searching.

The computer doesn't understand why a shape works. But it can find shapes that work. The human role shifts from designer to curator—setting up the search, defining the fitness criteria, selecting from results.

Sam Kriegman, one of the lead researchers, has called this "AI-designed organisms." The design is computational; the implementation is biological. The combination opens new territory.

Applications

What are xenobots good for?

Drug delivery. Tiny living machines could navigate the body and deliver drugs to specific sites. They'd be biocompatible (made of cells), potentially targeted, and could degrade safely when done.

Environmental remediation. Xenobots could be designed to collect microplastics or toxins, moving through water or soil and cleaning as they go.

Wound healing. Organisms that can move through tissue and promote repair. Living bandages that actively participate in healing.

Research. Understanding how cells self-organize, how behavior emerges from structure, how living systems can be designed. Xenobots are a platform for exploring life's possibilities.

Most applications are speculative at this stage. Xenobots are a proof of concept, not a product. But the concept they prove—that you can design living machines—has far-reaching implications.

The Safety Question

When news of self-replicating xenobots broke, some headlines were alarming. Self-replicating machines! Could they get out of control?

The researchers anticipated this. Xenobots have several built-in limitations:

No genome for replication. They can assemble offspring from external cells, but those cells have to be provided. They're not synthesizing cells from raw materials.

Limited lifespan. Xenobots live for days to weeks, then die. They can't reproduce indefinitely.

Environmental dependence. They only work in very specific conditions—the right medium, the right cell types. They wouldn't survive in the wild.

No evolution. Because their structure isn't encoded in a heritable genome, they can't evolve. A traditional organism that reproduced and varied could adapt to new environments. Xenobots can't.

The researchers argue that xenobots are actually safer than many synthetic biology systems because they lack the core features that make things dangerous: heritability, evolvability, environmental robustness.

Still, the principle raises questions. As we learn to design living machines, safety becomes a design constraint. Biosecurity isn't an afterthought; it's part of the engineering specification.

What Life Can Be

Xenobots are philosophically provocative.

For centuries, life was something you observed. Natural history documented the living world. Biology explained how it worked. But life itself was given—a phenomenon to study, not to design.

Xenobots suggest that life is more malleable than that. The same cells that make a frog can be rearranged to make a self-propelled blob. The "life" is in the cells, not the form. The form is up for grabs.

This raises questions:

What is life? If xenobots are alive (or at least made of living cells), what defines the category? Does it require evolution, reproduction, metabolism, or something else?

What is natural? Xenobots use natural cells but artificial designs. Are they natural or artificial? The distinction blurs.

What are we allowed to create? If we can design living machines, should we? Who decides the boundaries?

Xenobots don't answer these questions. They force us to ask them in new ways.

From Xenobots to...?

The xenobot project is early-stage exploration. Where does it lead?

More complex designs—using more cell types, more sophisticated structures, more capable behaviors. The current xenobots are simple; future versions could be far more elaborate.

Different source organisms—xenobots from human cells, or engineered cells, or synthetic cells. The frog cells were chosen for convenience, not necessity.

Integration with synthetic biology—xenobots with engineered genetic circuits, capable of sensing, computing, and responding. Living machines with computational control layers.

Hybrid systems—living components integrated with non-living scaffolds or electronics. Cyborg organisms that combine biological and technological elements.

The space of possibilities is barely explored. Xenobots are a first step into a much larger territory.

The Bigger Picture

Synthetic biology is learning to design at every scale.

At the molecular scale: engineered proteins, evolved enzymes, designed genetic circuits.

At the cellular scale: reprogrammed cells, minimal genomes, engineered pathways.

At the organismal scale: xenobots. Living machines designed from cells.

The progression continues. Design principles at each scale feed into the next. Understanding how to engineer molecules enables engineering cells. Engineering cells enables engineering organisms. Engineering organisms enables... what?

We don't fully know yet. We're inventing a discipline. The xenobots are one data point in a much larger exploration.

Life is becoming a design medium. We're just learning what's possible.

Further Reading

- Kriegman, S., Blackiston, D., Levin, M., & Bongard, J. (2020). "A scalable pipeline for designing reconfigurable organisms." PNAS. - Kriegman, S., et al. (2021). "Kinematic self-replication in reconfigurable organisms." PNAS. - Levin, M. (2021). "Life, death, and self: Fundamental questions of primitive cognition viewed through the lens of body plasticity." Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. - Bongard, J., & Levin, M. (2021). "Living Things Are Not (20th Century) Machines." Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.

This is Part 4 of the Synthetic Biology series. Next: "DNA Data Storage: Biology as Hard Drive."

Comments ()