The Zeroth Law: Why Temperature Makes Sense

Here's a question that seems stupid until you think about it: How do you know a thermometer is telling the truth?

You stick a thermometer in boiling water, it reads 100°C. You trust it. But why? The thermometer isn't measuring the water directly—it's measuring itself, then assuming that its temperature equals the water's temperature. That assumption is so fundamental that we don't even notice we're making it.

The assumption works because of the Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics. And without it, the entire concept of temperature would collapse.

The Law

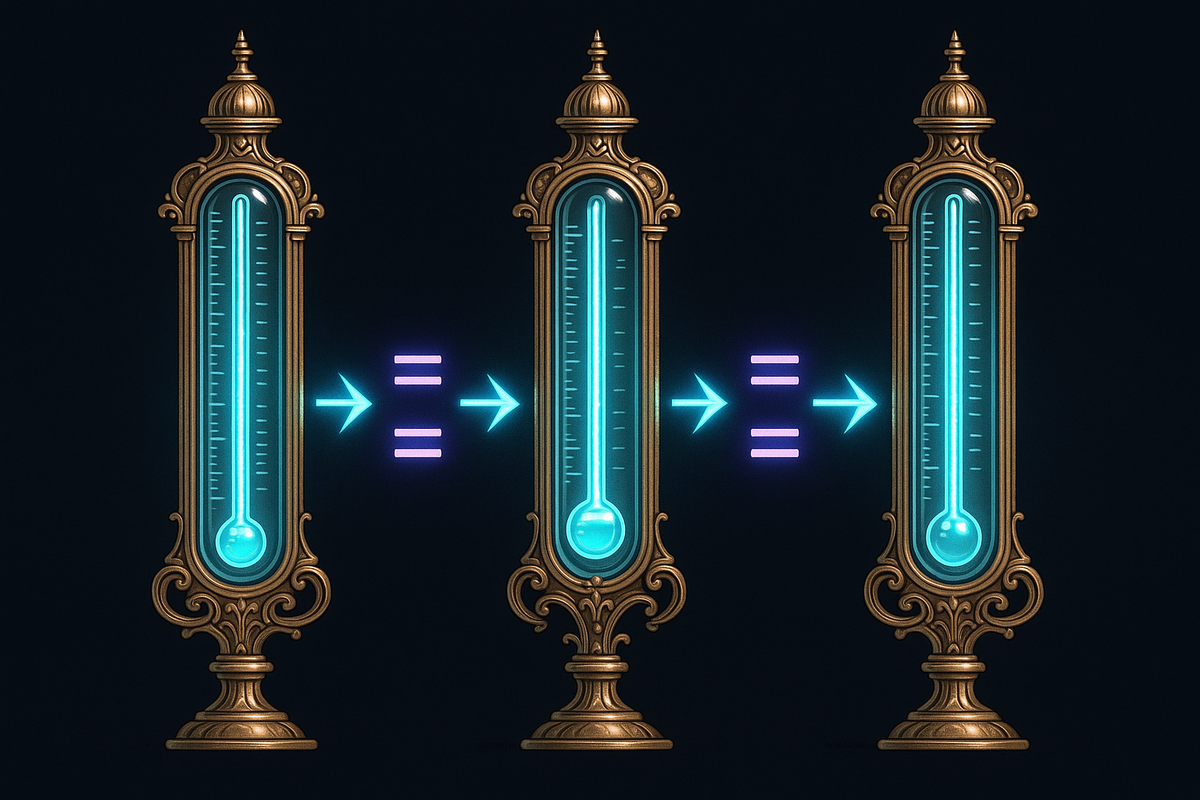

The Zeroth Law states: If system A is in thermal equilibrium with system B, and system B is in thermal equilibrium with system C, then system A is in thermal equilibrium with system C.

Written formally: If A ~ B and B ~ C, then A ~ C. Thermal equilibrium is transitive.

This sounds like a logical tautology. It's not. It's an empirical fact about our universe that didn't have to be true. There's no mathematical reason why transitivity must hold for thermal equilibrium. We just observe that it does.

The pebble: Temperature works as a concept because the universe happens to obey transitivity for thermal equilibrium. If it didn't, every measurement would be local, incomparable, and essentially meaningless.

Why "Zeroth"?

The Zeroth Law got its number because it was discovered last but proved more fundamental than the others.

The First, Second, and Third Laws were formulated in the mid-1800s. But in 1935, Ralph Fowler pointed out that they all assumed something they never stated: that thermal equilibrium is transitive, and therefore that temperature is a well-defined, universal property.

The other laws needed this assumption to work. So Fowler called it the "Zeroth Law"—logically prior to the First Law but discovered later. It's a naming convention that reflects how physics actually develops: we build on assumptions we don't notice until someone finally does.

What Is Thermal Equilibrium?

Two systems are in thermal equilibrium when no net heat flows between them. Put a warm object next to a cool one, and heat flows until they reach the same temperature. Once heat stops flowing, they're in equilibrium.

The Zeroth Law says this equilibrium relation is transitive. If the thermometer (B) is in equilibrium with the water (A), and later the thermometer (B) is in equilibrium with another substance (C), then A and C must have the same temperature—even if they never touched each other.

The pebble: The Zeroth Law is what makes thermometers possible. Without it, your thermometer reading after touching the water would tell you nothing about anything else.

Temperature as a Universal Property

Before the Zeroth Law was articulated, physicists implicitly trusted that temperature was universal. But "trust" isn't physics. The Zeroth Law makes it explicit: temperature is an equivalence class.

Every system at equilibrium can be assigned a number (temperature) such that systems with the same number don't exchange heat when brought into contact. The Zeroth Law guarantees this assignment is consistent and transitive.

Different thermometers—mercury, alcohol, thermocouple, infrared—measure temperature through different mechanisms. But they agree because the Zeroth Law holds. If transitivity failed, a mercury thermometer and a thermocouple might give different readings for the same object, with no way to say which was "right."

The Statistical Mechanics View

From statistical mechanics, the Zeroth Law emerges from how energy distributes among particles.

When two systems exchange energy, particles in the hotter system have more kinetic energy on average. Collisions transfer energy from high-energy particles to low-energy ones. This continues until both systems have the same average kinetic energy per particle—the same temperature.

The transitivity comes from mathematics: if system A has the same average energy as B, and B has the same as C, then A has the same as C. The Zeroth Law isn't mysterious from this view—it's a consequence of what "same temperature" means statistically.

The pebble: Temperature is average kinetic energy per particle. The Zeroth Law is just the transitive property applied to averages.

What If the Zeroth Law Failed?

Imagine a universe where thermal equilibrium isn't transitive. System A equilibrates with B at some "temperature." System B equilibrates with C at the same "temperature." But when you bring A and C together, heat flows.

In this universe: - Thermometers would only work locally - Temperature scales would be useless - The concept of "how hot something is" would depend on the comparison object - Climate science, cooking, engineering—anything requiring temperature measurement—would be impossible

The Zeroth Law isn't a logical necessity. It's an empirical gift. Our universe happens to work this way.

Historical Context

Temperature measurement preceded the understanding of what temperature is.

Galileo built early thermoscopes around 1600. Fahrenheit developed the mercury thermometer in 1714. But what were they measuring? Scientists talked about "degrees of heat" without a rigorous definition.

The kinetic theory of gases (1850s-1860s) finally connected temperature to molecular motion. James Clerk Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann showed that temperature is proportional to average kinetic energy. Only then did the implicit assumption—that temperature is universal and transitive—become explicit enough to state as a law.

Fowler named the Zeroth Law in 1935, but the physics community didn't widely adopt the name until the 1950s. Even fundamental laws take time to be recognized as fundamental.

Applications

Thermometer Calibration

When you calibrate a thermometer by placing it in ice water (0°C) and then boiling water (100°C), you're relying on the Zeroth Law. The assumption is that your thermometer, once equilibrated with the ice water, has the same temperature as any other system that equilibrates with ice water. Without transitivity, calibration would be meaningless.

Material Science

Different materials expand at different rates with temperature. Thermal expansion coefficients let engineers predict how bridges, rails, and electronics behave. This only works if "temperature" means the same thing across materials—which it does because of the Zeroth Law.

Thermal Imaging

Infrared cameras don't touch their targets. They detect radiation, infer temperature, and assume that this temperature is comparable to temperatures measured by contact methods. The Zeroth Law justifies this assumption.

The Philosophical Depth

The Zeroth Law is really a statement about equivalence relations. For something to be a well-defined property (like temperature), it must be: - Reflexive: A ~ A (everything is in equilibrium with itself) - Symmetric: If A ~ B, then B ~ A (equilibrium is mutual) - Transitive: If A ~ B and B ~ C, then A ~ C (the Zeroth Law)

The Zeroth Law provides transitivity. Reflexivity and symmetry are more obvious (you can't be out of equilibrium with yourself; equilibrium between two systems is mutual). Together, they make temperature an equivalence class property.

The pebble: The Zeroth Law is what promotes temperature from a local sensation to a universal, measurable property. It's the foundation that lets us do quantitative science about heat.

Connections

The Zeroth Law connects to the other laws:

First Law: Conservation of energy assumes we can talk about energy moving between systems. But "energy transfer as heat" requires a temperature difference, which requires temperature to be well-defined. The Zeroth Law provides that foundation.

Second Law: Entropy changes depend on temperature (dS = dQ/T). If temperature weren't transitive, entropy calculations between different systems would be inconsistent.

Third Law: Absolute zero is the same for all systems. That universality requires the Zeroth Law's transitivity.

Why You Should Care

The Zeroth Law is rarely taught well because it seems obvious. But "obvious" assumptions are where the deep structure hides.

Every time you check a weather forecast, adjust your thermostat, or take someone's temperature, you're relying on the Zeroth Law. You're trusting that "72°F" means the same thing in the weather report, your thermostat, and your body.

It does. But only because the universe happens to have transitive thermal equilibrium.

The pebble: The Zeroth Law is why science can be cumulative—why measurements made in one lab apply in another. Without it, physics would be local folklore, not universal law.

Further Reading

- Zemansky, M. W. & Dittman, R. H. (1997). Heat and Thermodynamics. McGraw-Hill. (Chapter 1) - Fowler, R. & Guggenheim, E. A. (1939). Statistical Thermodynamics. Cambridge University Press. - Reif, F. (1965). Fundamentals of Statistical and Thermal Physics. McGraw-Hill.

This is Part 2 of the Laws of Thermodynamics series. Next: "The First Law: Energy Cannot Be Created or Destroyed"

Comments ()