Systems of ODEs: When Multiple Quantities Change Together

Most real systems have multiple interacting variables. Temperature and pressure. Prey and predator. Position and velocity. Multiple chemical concentrations.

Each variable evolves according to its own differential equation, but the equations are coupled—each variable's rate of change depends on other variables.

That's a system of differential equations.

Standard form:

dx/dt = f(x, y) dy/dt = g(x, y)

Two equations, two unknowns. The system describes how x and y evolve together over time.

Why Systems Matter

Almost everything interesting involves multiple variables.

Mechanics: Second-order equations reduce to first-order systems. Newton's law F = ma becomes:

dx/dt = v (velocity is rate of change of position) dv/dt = F/m (force determines acceleration)

Two coupled first-order equations in x and v.

Ecology: Predator-prey dynamics (Lotka-Volterra):

dR/dt = αR - βRP (rabbits grow, get eaten) dF/dt = δRP - γF (foxes grow by eating, die naturally)

Two coupled equations in R (rabbits) and F (foxes).

Chemistry: Multiple reacting species:

dA/dt = -k₁AB dB/dt = -k₁AB + k₂C dC/dt = k₁AB - k₂C

Three coupled equations tracking concentrations.

Epidemiology: SIR model:

dS/dt = -βSI (susceptible → infected) dI/dt = βSI - γI (infected recover) dR/dt = γI (recovered)

Three coupled equations describing disease spread.

Single equations are rare. Reality is systems.

Linear Systems: The Foundational Case

A system is linear if the right-hand sides are linear in the variables.

General linear system (2D):

dx/dt = ax + by dy/dt = cx + dy

where a, b, c, d are constants.

Matrix form:

d/dt [x; y] = [a b; c d][x; y]

Or: dX/dt = AX, where X = [x; y]ᵀ and A is the coefficient matrix.

This is the foundation. Solve linear systems first, then tackle nonlinear.

Eigenvalue Method for Linear Systems

For dX/dt = AX, try exponential solutions: X = e^(λt)V, where V is a constant vector.

Substitute: λe^(λt)V = Ae^(λt)V

Cancel e^(λt): λV = AV

This is an eigenvalue problem: AV = λV.

λ is an eigenvalue of A, V is the corresponding eigenvector.

Find eigenvalues by solving: det(A - λI) = 0 (characteristic equation).

For 2×2 matrix:

det([a-λ b; c d-λ]) = 0

(a-λ)(d-λ) - bc = 0

λ² - (a+d)λ + (ad-bc) = 0

Solve for λ using quadratic formula. Each eigenvalue gives a solution e^(λt)V.

Example: Linear System with Real Eigenvalues

Solve:

dx/dt = x + 2y dy/dt = 3x + 2y

Matrix form: A = [1 2; 3 2]

Characteristic equation: det([1-λ 2; 3 2-λ]) = 0

(1-λ)(2-λ) - 6 = 0

2 - 3λ + λ² - 6 = 0

λ² - 3λ - 4 = 0

(λ - 4)(λ + 1) = 0

Eigenvalues: λ₁ = 4, λ₂ = -1

Eigenvector for λ₁ = 4:

(A - 4I)V = 0

[-3 2; 3 -2]V = 0

Row 1: -3v₁ + 2v₂ = 0 → v₂ = (3/2)v₁

Choose v₁ = 2: V₁ = [2; 3]

Eigenvector for λ₂ = -1:

(A - (-1)I)V = 0

[2 2; 3 3]V = 0

Row 1: 2v₁ + 2v₂ = 0 → v₂ = -v₁

Choose v₁ = 1: V₂ = [1; -1]

General solution:

X = C₁e^(4t)[2; 3] + C₂e^(-t)[1; -1]

Or componentwise:

x = 2C₁e^(4t) + C₂e^(-t) y = 3C₁e^(4t) - C₂e^(-t)

As t → ∞, the e^(4t) term dominates (unstable). The system diverges unless C₁ = 0.

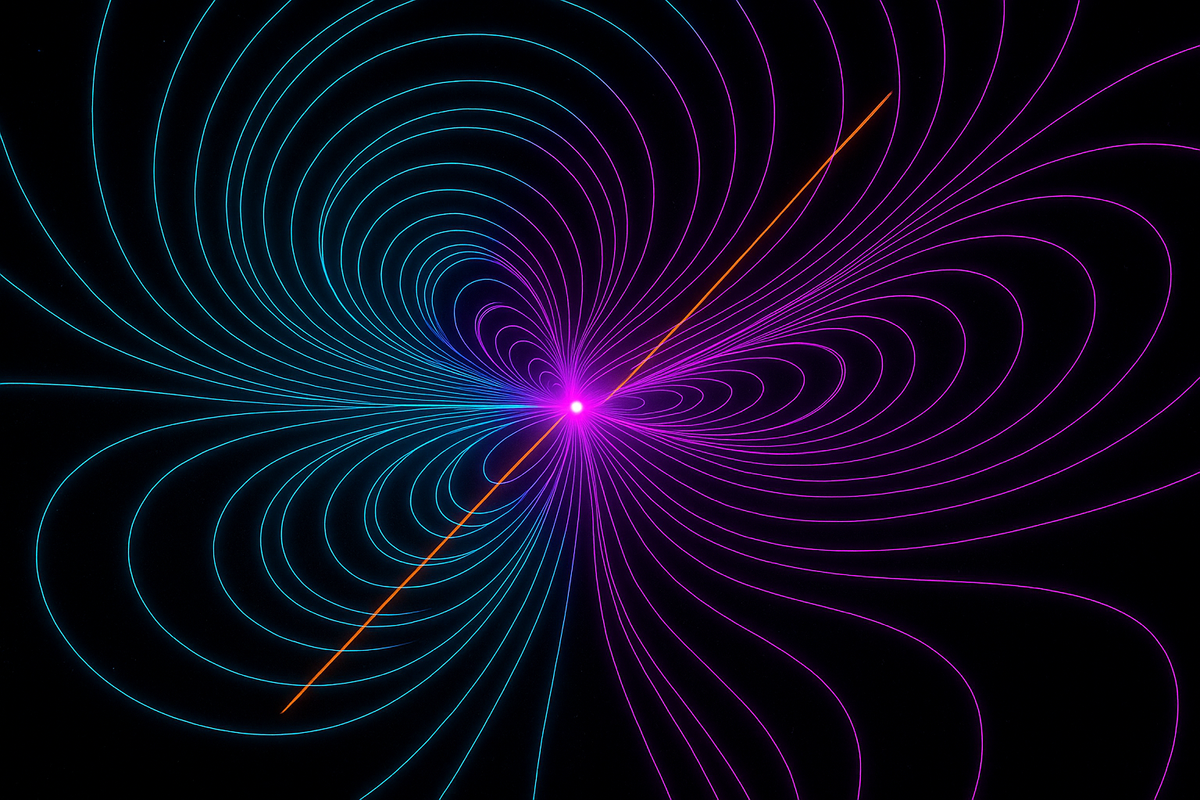

Phase Portraits

For systems, solutions are curves in the (x, y) plane—trajectories or orbits.

The collection of trajectories is the phase portrait. It shows how all initial conditions evolve.

For the example above:

- Trajectories either escape to infinity (if C₁ ≠ 0)

- Or approach origin along direction [1; -1] (if C₁ = 0)

The origin is a saddle point—stable in one direction, unstable in another.

Classification of Equilibria (2D Linear)

For dX/dt = AX, the origin is always an equilibrium (X = 0).

Stability depends on eigenvalues:

Both λ < 0 (negative real parts): Stable node. All trajectories → origin.

Both λ > 0 (positive real parts): Unstable node. All trajectories diverge.

λ₁ < 0, λ₂ > 0 (opposite signs): Saddle point. Stable in one direction, unstable in other.

Complex λ = α ± iβ:

- α < 0: Stable spiral (trajectories spiral inward)

- α > 0: Unstable spiral (trajectories spiral outward)

- α = 0: Center (elliptical orbits, periodic)

The eigenvalues determine everything.

Example: Oscillating System

dx/dt = -y dy/dt = x

Matrix: A = [0 -1; 1 0]

Characteristic equation: det([-λ -1; 1 -λ]) = 0

λ² + 1 = 0

Eigenvalues: λ = ±i (pure imaginary)

Solution: x = C₁cos(t) + C₂sin(t), y = C₁sin(t) - C₂cos(t)

Trajectories are circles around the origin (center). The system rotates forever—periodic motion.

This describes a harmonic oscillator in phase space.

Decoupling via Diagonalization

If A has distinct eigenvalues, you can diagonalize:

A = PDP⁻¹

where D is diagonal (eigenvalues on diagonal), P has eigenvectors as columns.

Change variables: X = PY. Then:

dY/dt = P⁻¹(dX/dt) = P⁻¹AX = P⁻¹APDY = DY

Now the system is decoupled:

dy₁/dt = λ₁y₁ dy₂/dt = λ₂y₂

Each equation is independent—exponential growth/decay. Solve trivially:

y₁ = C₁e^(λ₁t), y₂ = C₂e^(λ₂t)

Transform back: X = PY.

Diagonalization reduces coupled systems to uncoupled exponentials.

Nonlinear Systems

When the right-hand side is nonlinear:

dx/dt = f(x, y) dy/dt = g(x, y)

Analytical solutions rarely exist. You use:

- Linearization near equilibria: Approximate by linear system, analyze stability

- Phase plane analysis: Plot trajectories numerically, identify behavior

- Numerical integration: Euler, RK4, etc.

Linearization Near Equilibria

Find equilibrium points: solve f(x, y) = 0, g(x, y) = 0 simultaneously.

Near equilibrium (x₀, y₀), linearize using Jacobian:

J = [∂f/∂x ∂f/∂y; ∂g/∂x ∂g/∂y] evaluated at (x₀, y₀)

The linearized system: dX/dt = J·X (where X measures deviation from equilibrium).

Eigenvalues of J determine local stability.

Example: Predator-Prey

dR/dt = αR - βRF (R = rabbits, F = foxes) dF/dt = δRF - γF

Equilibrium: R = γ/δ, F = α/β (coexistence).

Jacobian at equilibrium:

J = [0 -βγ/δ; δα/β 0]

Eigenvalues: λ = ±i√(αγ) (pure imaginary)

Center—periodic oscillations around equilibrium. Rabbits and foxes cycle.

This is why predator-prey systems oscillate: the linearized system has imaginary eigenvalues.

Limit Cycles

Some nonlinear systems have limit cycles: isolated closed orbits that attract nearby trajectories.

Example: Van der Pol oscillator.

dx/dt = y dy/dt = -x + μ(1 - x²)y

For μ > 0, this has a stable limit cycle. Trajectories spiral toward a periodic orbit.

Limit cycles can't occur in linear systems—only in nonlinear.

Chaos

Some nonlinear systems exhibit chaos: sensitive dependence on initial conditions.

Example: Lorenz system (simplified atmospheric convection):

dx/dt = σ(y - x) dy/dt = x(ρ - z) - y dz/dt = xy - βz

For certain parameters, trajectories never repeat and diverge exponentially from nearby initial conditions.

Chaos means long-term prediction is impossible, even though the equations are deterministic.

Numerical Methods for Systems

Extend single-equation methods (Euler, RK4) component-wise.

For dX/dt = F(X):

Euler: X_{n+1} = X_n + h·F(X_n)

RK4: Same structure, applied to vector X instead of scalar y.

Every numerical method for single equations generalizes to systems.

Higher-Order ODEs as Systems

Any nth-order ODE converts to a system of n first-order ODEs.

Example: y'' + py' + qy = 0

Let x₁ = y, x₂ = y'. Then:

dx₁/dt = x₂ dx₂/dt = -qx₁ - px₂

This is a 2D linear system. Solve via eigenvalues (same as characteristic equation method).

Second-order ODE ↔ 2D system. The characteristic equation of the ODE equals the eigenvalue equation of the system matrix.

Conservation Laws

Some systems conserve quantities.

Example: Hamiltonian systems

dx/dt = ∂H/∂y dy/dt = -∂H/∂x

The Hamiltonian H(x, y) is conserved: dH/dt = 0.

Trajectories lie on level curves of H—closed orbits (often).

Harmonic oscillator is Hamiltonian with H = (x² + y²)/2 (energy conservation).

Poincaré-Bendixson Theorem

For 2D continuous systems, long-term behavior is limited:

Trajectories either:

- Approach an equilibrium point

- Approach a limit cycle

- Wander chaotically (impossible in 2D!)

Chaos requires at least 3 dimensions. In 2D, trajectories can't cross (uniqueness), which constrains behavior.

This is why the Lorenz system (3D) can be chaotic, but predator-prey (2D) cycles.

Matrix Exponential (Advanced)

For dX/dt = AX, the general solution is:

X(t) = e^(At)X(0)

where e^(At) is the matrix exponential:

e^(At) = I + At + (At)²/2! + (At)³/3! + ...

If A is diagonalizable (A = PDP⁻¹):

e^(At) = Pe^(Dt)P⁻¹

where e^(Dt) is diagonal with entries e^(λᵢt).

This formalizes the eigenvalue method.

Practical Workflow

To solve a system:

- Linear, constant coefficients: Find eigenvalues/eigenvectors, write solution as linear combination.

- Nonlinear: Find equilibria, linearize via Jacobian, analyze stability. Use numerics for full trajectories.

- Numerical: Implement RK4 or use library (scipy.integrate.solve_ivp, MATLAB ode45).

- Phase portrait: Plot trajectories for various initial conditions to visualize behavior.

Summary

Systems of differential equations model interacting variables. Linear systems reduce to eigenvalue problems. Nonlinear systems require linearization, phase plane analysis, and numerics.

Key concepts:

- Eigenvalues determine stability

- Phase portraits visualize dynamics

- Linearization analyzes local behavior near equilibria

- Numerical methods handle nonlinearity and complexity

Next: Laplace transforms, an algebraic technique for solving ODEs without direct integration.

Part 10 of the Differential Equations series.

Previous: The Bernoulli Equation: A Clever Substitution Next: The Laplace Transform: Turning Calculus into Algebra

Comments ()